FOURTH SUNDAY IN LENT | MARCH 10, 2024 | John 3:14-21 (RCL) | David Zersen |

And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life. “Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. Those who believe in him are not condemned; but those who do not believe are condemned already, because they have not believed in the name of the only Son of God. And this is the judgment, that the light has come into the world, and people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil. For all who do evil hate the light and do not come to the light, so that their deeds may not be exposed. But those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God.”

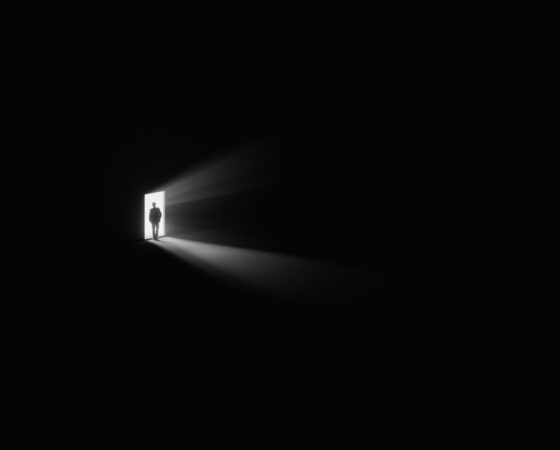

THE LIGHT WE CANNOT SEE

Is there a light that the human eye cannot see? Astronomers wonder, for example, if there is light in our universe beyond that which a star or a nova can project. If all such objects were absent, even the dust particles in space that reflect light, would everything then be dark to the naked eye? Astronomers believe that although the distances are vast and the answer can’t be proven, they theorize that there is an Extragalactic Background Light or EBL that glows. Think of it – a light that we cannot see, but it’s still there!

There is light – and the darkness cannot extinguish it.

I like the thought that there is always light, even when darkness may threaten to overcome it. I think of the art of Mark Rothko (1903-1970), an abstract expressionist painter, who explored tensions between light and darkness in his mid-20th century artwork. His Rothko Chapel at the Menil campus in Houston, Texas, is world famous for its attempt to involve the visitor in reflections that border on the spiritual. Large canvasses of dark colors fill the vertical spaces. It would be a “black hole”, one might say, were it not for occasional skylights that allow beams of light to play with the blackness of the interior. What does it mean? Does it mean anything? Analysts have seen “ethereal luminosity” and a “transformative glow” in the chapel. Visitors can enter a dialogue with the light and “transcend the boundaries of art to engage in the spiritual depth of human experience.”[1] Perhaps.

Perhaps, however, there is more to spiritual exploration than stillness and contemplation, than a vague transcendence or an inner dialogue. After all, Mark Rothko, facing personal despair, did commit suicide before the chapel was dedicated in 1971. What if the contemplation of the degrees of darkness – purple, black, and brown – produce only starkness, a void, remorse, even emptiness? Admittedly, these may be only my questions.

Nevertheless, one may wonder whether the One who spoke light into the black abyss in the creation story does not have more in mind for us than such “abstract expressionism” can provide. What if, for example, we were to let the New Testament’s speak to us about darkness and light. Paul asks the Corinthians to think about it, to ask whether light and darkness can have anything in common. (2, 6:14). And given that people who have not fully grasped the light may still live in the dark, he says to the first Christians in Rome, “Put aside the deeds of darkness and put on the armor of light” (13:12). Darkness, for Paul, can involve actions like drunkenness, sexual licentiousness, dissension, jealousy – all the things that contribute to a life that we may prefer to keep hidden from those we love and respect (13:13). Darkness, in the biblical sense, then, is not something vague and amorphous that we can contemplate casually. It is something we are encouraged to avoid at all costs.

But what about light? Could light in the biblical sense be some casual, superfluous spirit that hovers over the darkness in our lives and encourages us to think about a little transcendence? Our text says that the light is intentional. It was given to give us life. It came into the world to challenge the darkness. It helped all who trust in the “Light of the world” to become light in themselves. And by being light, we may find ourselves empowered to act. In contrast, the author of 1 John writes, “Anyone who claims to be in the light but hates his brother is still in the darkness.” (2:9) We are no longer what we could have been, but we are what we entrusted to become – through Christ alone. John writes to you and to me (John 1: 1:5):

“This is what we heard Him tell us. We are passing it on to you. God is light. There is no darkness in Him. If we say we are joined together with Him but live in darkness, we are telling a lie. We are not living the truth. If we live in the light as He is in the light, we share what we have in God with each other. And the blood of Jesus Christ, His Son, makes our lives clean from all sin.”

And you and I live in that light, do we not? From the day of our baptisms, the light of Christ presented with the baptismal candle, introduced us to the power of that light which continues to work in us through the preached Word, through the Word who is the body and blood, through the Word that shapes the love we received through Christian parents, relatives, and friends. As John says, “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness cannot extinguish it”. (1:4-5)

There is light – that we avoid at our peril

There is now light in us and there is light in others – and it may be the very light of Christ shining through our words and actions as well as those of others. But what if, like the light in outer space that we cannot see, or the light we may not see in Mark Rothko’s art, it may seem at times that there’s no light at all? Sometimes it’s a black day. Sometimes it seems like the end of the world. For some, there is the choice to just end it all. But there is light, even if we have not seen it.

The 2014 novel by Anthony Doerr, which by the way, won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, has a title related to these reflections, All the Light We Cannot See. The story is set in St. Malo, France during World War II. Because it’s also been made into a Netflix four-part series, I can visualize it for you. It’s a war story, like many others, and it has its share of violence, hatred, and darkness. However, Doerr has given us something more. In the main characters, he offers light that we have no right to expect. On the one hand, there is Werner Pfennig, a 14-year-old orphaned boy who is very bright and is sent by the Nazis from the orphanage to capture someone in St. Malo who is transmitting radio reports to the French resistance. His co-star is Marie LeBlanc, a blind girl, sightless in real life, who despite her personal tragedies in the war, has learned how to transmit the reports on the radio that young Werner has been drafted to find and silence. Behind the façade of desperate flights and slaughter, there is creative survival, desperate striving to help another in need and, perhaps, in the end, there is a love story, cemented with a closing kiss!! (at least in the film made from the book).

The story is realistic, cruel, and heartbreaking, but in the darkness, there is light that can’t be seen unless one takes the time to explore what’s really happening, what’s at the heart of matter. And this is what I want you to hear. Even though St. John reminds us that we have become light because we belong to Jesus, we often refuse to see past the dark façade in the lives of our brothers and sisters. Werner did kill people and so did Marie! We easily identify those who are too fat, who dress slovenly and wear outlandish hairstyles. Tsk tsk. There are those who say thoughtless things, who don’t seem to care if we live or die, who don’t belong to our class of people. Shame on them! They may, however, like Werner and Marie, have significant gifts or helpful insights or caring feelings we could never know unless Anthony Doerr helped us to find them or because we’ve been staring at a big black canvas, unaware of subtle beams of light penetrating us and others in our world. Have we tried to find the light that has overcome the darkness even in our colleagues, our associates, and our neighbors? Paul writes to us, “Our knowledge of others is incomplete. “Now we see only partially. One day we will have a fuller understanding.” (1 Cor. 13:12)

There is now nothing so bright, dear friends, as the powerful light that beams from the cross of Christ. Many have claimed in their darkness that to ascribe such a tragedy, the murder of one’s son, to the very hand of God, is to imagine a tyrant with whom they will have no truck! As Paul writes to the Corinthians, “Unbelievers cannot see the light of the Gospel of the glory of Christ.” (2, 4:4) But it is our privilege to have seen this glorious light and to trust that it alone can penetrate the darkness created by our own failures, yes, by our own sin. In the darkness at Calvary, we have seen this light. We have understood how in life lived and ultimately surrendered for others, there is the only light that can overcome the darkness. In the light streaming from Calvary, we discover what we humans otherwise cannot see. We have seen a light that makes life worth living; a light that shines brightly when we seek ways to love and care for one another.

Hymn/Solo: “Christ be our Light.”

—

David Zersen, D.Min, Ed.D., FRHisS

President Emeritus, Concordia University Texas

zersendj@gmail.com

[1] https://christian.net/arts-and-culture/why-are-the-paintings-in-the-rothko-chapel-so-dark/