THE RESURRECTION OF OUR LORD | Easter Sunday | MARCH 31, 2024 | Mark 16:1-8 (RCL) | David Zersen |

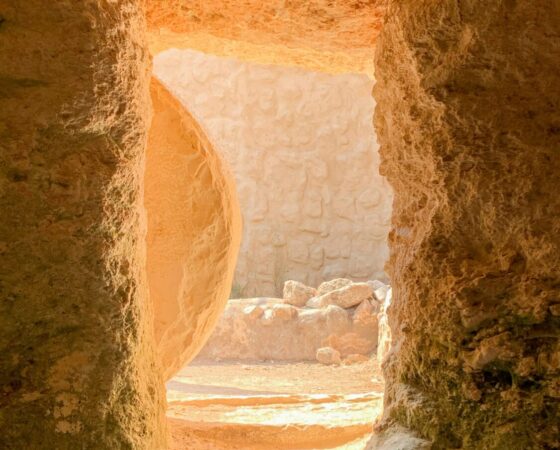

When the sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene and Mary, the mother of James, and Salome bought spices so that they might go and anoint him. And very early on the first day of the week, when the sun had risen, they went to the tomb. They had been saying to one another, “Who will roll away the stone for us from the entrance to the tomb?” When they looked up, they saw that the stone, which was very large, had already been rolled back. As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man, dressed in a white robe, sitting on the right side; and they were alarmed. But he said to them, Do not be alarmed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him, just as he told you. So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.

OVERCOMING EASTER FEAR

In the 1980s, for about eight years, a TV series called Dynasty covered the story of the Carrington family. By 1985, it was the #1 show in the United States, and it spawned successor shows after its demise. There’s something about family successions that we find interesting. As we look back to our ancestors with whom we comprise a kind of dynasty, I wonder what Easter celebrations looked like in your families decades ago, centuries ago. Did everyone dress up in their Easter finest, or as has become the custom in more recent years, did people wear whatever they had on when they finished cleaning out the garage or scrubbing the floor? (That’s supposed to be funny!) Our Easter trappings, clothes, and dinner preparations, down through the years, were intended to have significance. The nature of the celebration had much to do with the Easter story, the message that Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified at the instigation of violent mobs, rose from the dead. His resurrection was God’s proof that murder, evil in general, and savage hatred would not have the final word. For all those who believe that Jesus is our Messiah, the one who took the death that should have been ours and gave those who trust in him a life that lasts forever. That is good news–and that’s why on Easter Day, the celebration of Jesus‘ resurrection, many of us, for lengthy dynasties, have been dressing up, decorating our homes, eating grandly, and shouting in response to “Christ is risen,” “Christ is risen indeed”!

Looking at the setting Mark remembers for us

I would not like to throw ashes on that celebration because I also like to sing “Good Christian Friends, Rejoice and Sing.” However, the Gospel text for this year, Mark 16: 1-8, raises questions for us about why the earliest disciples may not have been as joyful as we would like to be. Mark is reputed to be our earliest Gospel, the shortest one, and the one having the shortest Easter story. It says that three women fled from the empty tomb in terror and amazement. They said nothing to anyone about what they had seen because “they were afraid.”

This text has caused interpreters problems for generations. Why are we celebrating the meaning of Christ’s resurrection for us when the women who entered the empty tomb were terrified? I would like to suggest that we need to appreciate what they were afraid of and whether, to some degree, that fear should be our own. Several interpretations have been given for their fear. On a somewhat humorous note, some interpreters have said that because women are telling this story, it ought to be believed! In first-century culture, a report from women was less likely to be believed than one from men. The fact that Mark passes on this account at all tells us that he was certain about its veracity.

Some scholars think that because Mark’s earliest account is shorter than what Matthew and Luke report, a section of it may have been lost—or even deleted. However, there are good reasons for

taking Mark at his word. There is a reason why an otherwise celebratory account of death being destroyed has become a cause for terror and amazement.

For a moment, let me reflect with you about why stories are told at all. Usually, history is told from the standpoint of the victors, not by the losers. Our own stories that are embarrassing tend not to be shared, while those that portray us in a positive light are told with gusto. We face this in our culture today because the stories that were told in the dominant U.S. culture did not always agree with the stories told in minority cultures. What is remembered about the Native Americans is often fanciful and romantic, while the Native American memories of history in the U.S. have been less positive. The desire for many in the Black community to shout “Black Lives Matter” can result from the fact that their representatives have seen themselves more as victims than as victors in American history.

The same perspective was shared by many Jewish people of Jesus’ day. They saw themselves as underdogs to the Romans and to well-placed Jewish leadership. Jesus‘ message often challenged the hypocritical and self-righteous lifestyle of the Jewish leadership. Jesus essentially attacked the lifestyle of those who put their faith in swords, in retaliation, in revenge, and in abiding hatred. The very perspectives that made Rome strong and the vassals of Rome acceptable to themselves were being undermined. And the common people, we are told, heard Jesus gladly.

They followed the one who taught them to love, not to hate, to pay Caesar what he was owed, to forgive seventy-times-seven, to trust God above all, and to seek a Kingdom in which they would have a place. When their leader was murdered, and his grave was empty, what were they to make of this? I think that Mark has it right. The victim, their leader, was dead, and they were alone. What kind of story does one write about that?

Looking at our setting and our future with Christ

The challenge for you and me today, in the light of Christ’s resurrection, is to ask ourselves how we want to write history. For the leadership of Jesus’ day, history had always been written from the standpoint of the victors. Jesus was dead; there would be no more trouble for him and his followers. For Jesus’ followers, however, and it took some time to grasp this, the resurrection was to be a new history, history written from the viewpoint of the victim! Initially, the suppressed people came to understand that the power structure had changed and that the leaders of the world had their way. Gradually, however, they said, “Wait a minute! The tomb is empty. What does it mean? Really? Oh my God!”

When it settled in, this is what it meant. Jesus had said that if you put your faith in the world’s order, then you die with it! If you put your faith in power, in militarism, in revenge, in hatred, then there’s nothing worth living for. You have no future if you believe that the strong are the best and the weak are worthless. Do we do this? Do you do it? But if you put your faith in the order that Jesus brings, something really scary happens. Jesus stands before us and says, “Peace be with you”! He invites us to consider a new way in the light of the resurrection. A new life after the life that leads to death. He invites us to consider a new way to be human, a new way to practice religion and a new way of ordering our economics and politics. Can we grasp it?

Fighting the fear of Easter

You see, the real fear at Easter is how to enter tomorrow with a new vision. I fear that too many people in this so-called secular age have no grasp of that new vision and the excitement it can bring. Percentages of people annually drop out of the Christian community and become “nones”—those who have no ties to the church. What they typically reject is superficial.

They think they want to be free, not to follow rules, practices, ordinances, laws, order. “Freedom,” we heard many cry when the call went out to support one another, to love one another, to avoid infecting one another with viruses: “We want to be free from rules,” they cried. What it really meant, however, was being free from obligations to be part of a community to do just what they wanted to do. This is the challenge Jesus calls us to in the new post-resurrection era. It is a challenge to love one another as he has loved us and to care as much about the health, welfare, and hope of others as we hope that they care about those things in us.

Mark is right with his Easter ending. It can be a scary thing to reorient our faith and live according to the Kingdom’s dawn that Jesus rose to proclaim. We are to be agents for the continuation of the Good News, to step out in faith. You see, the resurrection is not an event that stopped at an empty tomb in Jerusalem—something to cheer about. That is the scary part. It begins a movement. An intention that wants to be bold and unafraid. Let Jesus draw us to surprising new beginnings. Look past your Easter finest and seek a way to fight the fear of taking hold of a new resurrected life.

—

David Zersen, D.Min., Ed.D., FRHistS

President Emeritus, Concordia University Texas

zersendj@gmail.com